Long-term investors should stay away from most bonds for the foreseeable future.

Last summer, Colby Davis explained why portfolio managers might want to buy bonds that yield 2%. At the time, I was suspicious, but it felt premature to argue against it.

Since then, yields on 30-year government bonds have dropped to 1.44%. That means bond prices went up. His advice worked well as a hedge against pandemics.

Inflation expectations have dropped along with those yields.

30-year TIPS have an expected yield of -0.045%.

That implies expected CPI inflation of less than 1.5% over the next 30 years, and that, adjusted for inflation as measured by the CPI, investors who buy 30-year government bonds now should expect to lose wealth if they hold to maturity.

So why are investors buying bonds at these prices?

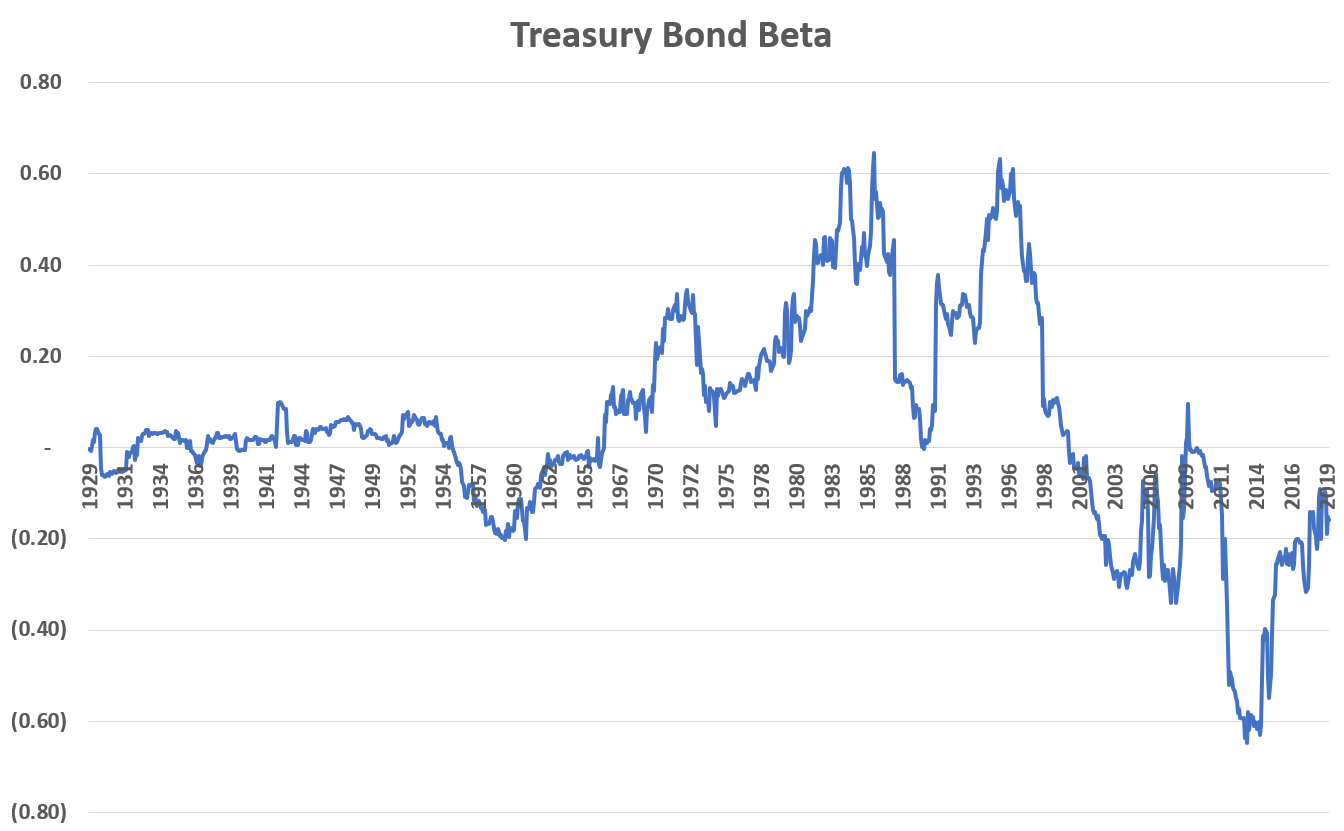

A key part of Colby’s argument is contained in his graph of bond beta:

That shows that for the past 20 years, treasury bonds have been a good way to diversify risk, since bonds have gone up when stocks went down.

But what about the past 20 years has been special, and why should we expect it to continue? Why should we overlook the previous 33 years (1967-2000), during which bonds added to the risk of stocks, or the many decades before that when there was no clear pattern? I’ll suggest that long-term investors will do better by expecting the past century to provide better evidence of future patterns than a mere 20 years of evidence.

Colby writes:

Since the new millennium the dollar, being the reserve currency of the world, has become a negative beta asset, which drives its equilibrium interest rate below its inflation rate, and so short-term deposits and debts denominated in dollars (and yen, and euros, and francs) such as treasury bills now lose money in real terms. Just as the cost of securing and insuring gold was just part of the overhead of running a bank back in the old days, so too is the depreciation associated with holding deposits in a reserve currency simply the cost of doing business today in a stable, prosperous, globalized economy.

Hmm. What happened in 2000 to enable that?

Maybe US budget surpluses convinced people that the US government was acting responsibly? But that evidence can hardly outweigh the more recent evidence of US fiscal irresponsibility, and ineptitude at dealing with pandemics.

Maybe the rising importance of Silicon Valley impressed investors? I can imagine that investors expect that to lead to the US tax base becoming a world-dominating powerhouse a few decades from now, when our robot overlords, or Age of Em cities, are owned by Silicon Valley companies. But I’m having trouble finding evidence of any actual investors thinking anything close to that – even if ownership of those industries is really important, there’s plenty of opportunity for other countries to compete, and some uncertainty in the connection between wealthy industries and a trustworthy currency.

Colby’s phrase “the reserve currency of the world” has to be somewhat misleading, because it’s not just 2 or 3 leading currencies that exhibit this pattern of low interest rates and negative beta. I see similar patterns with the Danish krone, and the Swedish krone. Those don’t seem to fit the standard notion of a reserve currency. In fact, those currencies (plus the euro and the yen) suggest that when nominal interest rates become negative, the negative beta benefit weakens. Bonds denominated in those currencies still went up when stock markets were crashing, but those bonds quickly returned to their February levels, while stock markets are still down more than 10% from their February highs. I.e. once yields become negative, any further increase in bond prices is unsustainable.

My explanation for low bond yields is not dollar-centric or related to reserve currency status. What I see is that central banks around the developed world erred on the inflationary side for decades, up until 1980 or so. Then an international consensus, among the people who influence those central banks, led to reversing those mistakes, and eventually erring in the other direction.

That led to fairly steady increases in demand for those currencies, as they became increasingly safe stores of wealth. And that increased demand increases the value of the currencies (at least if the central banks have any biases toward a slow, steady growth of the money supply), i.e. it reduces the inflation rate. So there’s a feedback loop that’s self-reinforcing, at least on a time scale of months, maybe longer.

How long can that feedback loop last?

There’s a limit to how big a fraction of total investment people can hold as dollar-like assets. E.g. it probably can’t exceed 100%. That means that at some point, the growth in demand for dollar-like assets will slow to no more than the growth in total wealth. It would be hard for the feedback loop to continue past that point, since ordinary increases in the money supply will suffice to produce as much inflation as a central bank is likely to target.

A more likely way in which the feedback loop might change is that central banks might change their policies.

The Fed has been undershooting its 2% inflation target for most of the past 8 years. Markets are suggesting that’s somewhat likely to continue for most of the next 30 years (which is as for out as the relevant bonds extend). Yet history suggests that central banks tend not to err in the same direction for much more than 20 or 30 years at a time. If for most of a central banker’s career, the central bank has been erring in one direction, and critics of the central bank have focused a fair amount of attention on that pattern, then it’s quite tempting for that central banker to support policies which ensure that any errors are in a different direction. So I suspect tha markets are mildly suffering from something like recency bias.

If the Fed switches from generating low inflation to generating high inflation, then dollars will become a less safe investment, and demand for dollars will decline, possibly creating a feedback loop that works in the opposite direction as the current one. I.e. reduced demand for dollars causes inflation, to which the Fed reacts by trying to keep the money supply and/or interest rates stable, rather than focusing directly on the best inflation forecasts.

If inflation becomes a bigger problem than deflation, then the correlation between stocks and bonds will likely go to zero, or become positive. That would eliminate a key reason for holding bonds. I’ll guess would cause bond prices to drop enough for inflation-adjusted bond yields to go up to 1 or 2 percent. That’s in addition to whatever decline in bond prices is needed to adjust for inflation.

If the current pandemic produces economic conditions that resemble wartime, the inflationary process could be fairly rapid. But I wouldn’t want to give that scenario more than a 10% chance. Most of the signs that I see suggest the virus will be contained to tolerable enough levels that only about 1% of the population gets mobilized for emergency jobs such as testing, tracing, and vaccine development, and the rest of us gradually resume our normal careers and the usual partisan excuse-making.

A more likely scenario is a gradual increase in inflation and interest rates over decades, with a long, slow decline in bond prices, as in the 1950-1980 period.

In fact, there are a fair number of similarities between 2020 and 1950 that hint to me that the bond market is in for something like a rerun of the 1950s, i.e. a nearly steady decline in bond prices. The 2008 crash and economic downturn look like the 1937 crash and downturn. They were followed by 12+ years of relatively low and stable government bond interest rates. Do the differences between WWII and the current pandemic outweigh those similarities? My intuition says no, but I can’t articulate a strong reason for that.

This doesn’t look like the kind of bubble that will have a sharp peak like the cryptocurrency bubble or the dot com bubble. Many bonds have been accumulated by pension funds, trust funds, the Chinese government, etc., and they’ll be pretty cautious about changing their strategies, as they won’t want to stand out as being different from other fund managers.

Colby may well be nimble enough to switch out of bonds shortly after the optimal time. But don’t think of bonds as a safe enough asset that you can buy and then forget about them for years.

I have not yet sold short any bonds. I expect to do so sometime within the next year.

P.S. Rereading Colby’s post led me to what looks, in hindsight, like a self-defeating prophecy:

To my mind, then, it makes sense that the market should be less volatile now than ever before. The world is just a less risky place these days.

Investors (including me) went a bit overboard on believing this, and that caused us to be less prepared, and to not have enough cash to buy at the March lows. If most investors had believed that a serious pandemic was still possible, there would have been less panic selling – partly because stocks wouldn’t have been quite so high to start with, and partly because investors would have been more willing to hold stocks through the decline.

> The world is just a less risky place these days.

That sure isn’t what it looks like to me. (Even pre-covid.) Is that just me?

Bruce, you’re presumably paying attention to different things than the typical professional investor.

Recessions have been less frequent recently. Australia has gone 29(?) years without one, and China’s growth has been about as steady as that. It seems likely that that’s in part due to better monetary policy, and that US monetary policy has had milder improvements of the same nature.

Wars have become less frequent.

Virtually all diseases that investors think of as preventable were kept from causing much harm, presumably by competent experts: Ebola, SARS, the 1976 swine flu outbreak, various bird flus all seem to have been stopped from spreading in the US. The 2009 swine flu pandemic didn’t cause enough harm to have an obvious effect on the market. I forget what happened with the MRSA super bugs that we’re occasionally warned about.

Diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s don’t get counted because few investors notice that there are societies that are virtually free of those epidemics, and they’re not changing enough to cause stock market volatility.

I think that covers most of the problems that have caused stock market declines over the past century or so. That obviously doesn’t produce a perfect model, but it usually works well.

Pingback: The Recent Surge in Inflation | Bayesian Investor Blog

Pingback: Investing Amid Low Expected Returns | Bayesian Investor Blog

Pingback: Bank Failures | Bayesian Investor Blog