[Highly speculative, and rather near the fringes of my expertise].

I’ve previously mentioned that medical studies on mice may have produced poor results due to the use of unnatural environments (cold stress, and the lack of burrow-like protection from predators).

Now I notice that standard rodent food has suspiciously high methionine levels.

E.g. this formula, which has artificially added methionine, and a glycine/methionine ratio of 1.46. Compare that to the diets of adult wild animals, which look to me like they’re around 2 for carnivores, and higher for most herbivores.

I also see this list of standardized formulas, which doesn’t try to look much like a natural diet. It looks to me like only one of those formulas has a glycine/methionine above 1.0 (the one that mentions low methionine levels in the name).

Apparently many mouse studies use proprietary standard chows that come from seeds, fish meal and animal byproducts. Those will have higher glycine/methionine ratios, but they are usually undocumented.

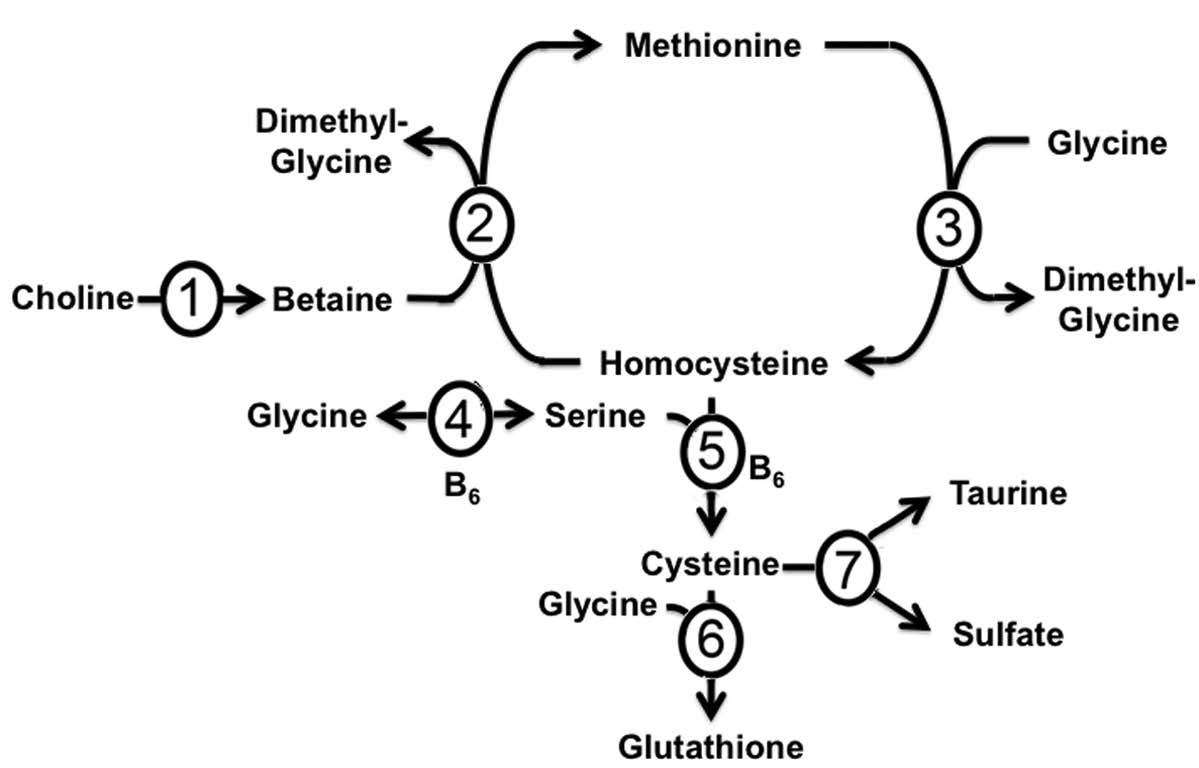

Glycine and methionine share a metabolic pathway, which suggests that the relative amounts of glycine and methionine might matter:

There’s some literature supporting the importance of glycine/methionine ratios:

Thus, altered ratios of Arg:Lys or Gly:Met offered beneficial influence on the lipid profile and plasma levels of ADMA, SDMA and homocysteine in hypercholesterolemic rats. Optimal beneficial effects, among ratios tested, was observed when Arg:Lys and Gly:Met ratios were maintained in ratios of 1:1 and 2:1, respectively.

Glycine supplementation extends lifespan of male and female mice, and methionine restriction tends to extend lifespan in a number of species.

This plausibly mean that some treatments look healthy for mice simply because they counteract the harm done by high methionine and/or low glycine. Maybe anything that causes calorie restriction helps counteract the harm from methionine.

Does anyone know why they add methionine?

My cynical initial guess was that they saw that methionine was an essential part of our diets, and, like too many consumers who buy nutritional supplements, they assumed that more is better for any such nutrient.

A more likely hypothesis is that methionine seems to speed up growth in young animals, and only seems to be harmful later in life. So methionine might reduce the time and/or cost of many experiments, while only interfering with a modest fraction of experiments.

The paper Amino acid requirements of the growing mouse (John and Bell, 1976) is a commonly cited source. It measures growth for 14 days after weaning. I.e. they seem to have focused on how fast young mice grow, and paid little or no attention to any effects on old mice.

If I’m reading their table 1 correctly, they and used a diet with 1.295% glycine, and after trying methionine levels in the range of 0.208% to 0.624%, they chose to recommend 0.52% methionine, for a glycine/methionine ratio of 2.49. Most standardized diets that I see follow the methionine advice somewhat closely, and use a much lower glycine level than the John and Bell study used. Hmm, maybe it’s just that nobody cares much about glycine levels, since they’re classified as non-essential?

I hope that people who study aging in mice pay a bit of attention to this.