“Transitory Inflation”

Many pundits are arguing that this year’s inflation is due to temporary pandemic-related problems.

I expect that they’re half-right – we’ve got a one-time pandemic-related burst of inflation, but it’s likely to be bigger than pundits imagine, and the price changes are unlikely to be reversed much when the effects of the pandemic fade.

Also, the presence of one-time effects shouldn’t reassure us about the absence of longer-term pressures.

When evaluating inflation, I focus mainly on the supply of and demand for money. Supply chain problems may be important for many purposes, but they don’t explain a general pattern of dollars becoming less valuable.

The Fed wisely increased the money supply in the spring of 2020, to accommodate an abnormal surge in demand for dollars and dollar-like investments. By which I mean that people wanted more of their assets to be in cash / checking / money market accounts, as opposed to stocks, real estate, cryptocurrency, etc.

Yet they did so without having a competent plan for undoing that when the pandemic was over.

Some of the problem is likely to be that they focus too much on interest rates as an indicator of whether their policy is loose or tight.

Possibly the main problem is that they felt a need to commit in 2020 to a long period of low interest rates, when what we really needed was for them to commit to adjusting the money supply as needed to stabilize something like the TIPS spread (inflation forecast) or NGDP futures. Now the economy is acting more stimulated than most people could have imagined 18 months ago. The Fed is stuck with honoring that commitment in order to maintain their credibility, even though current economic conditions call for something different.

The demand for money at the start of the pandemic was high because people became unusually risk averse. That risk aversion is mostly returning to normal now, at least judging by how people handle their money. (It looks different if I focus on phenomena such as mask wearing and verification of vaccine status, but I expect those are mostly signaling rituals that tell us little about the risk-aversion that’s relevant to finance.)

The economy might even be a bit more risk-loving these days, as the pandemic and the Fed’s response to it have transferred a good deal of wealth from cautious investors to the kind of people who buy cryptocurrency or GameStop.

How Much?

What would happen if the Fed just undid the stimulus of 2020 and shrank the money supply back to where it would have been in the absence of a pandemic? My guess is that it would produce a brief period of deflation, with a short recession of hard-to-predict magnitude. That seems unlikely to be the optimal policy.

Much has changed about people’s demand for money, due to changing financial situations, changing evidence about inflation, changing evidence about the stock and real estate markets, etc. I can’t adequately evaluate those effects by modeling how much demand for money there ought to be. I need good, recent empirical evidence.

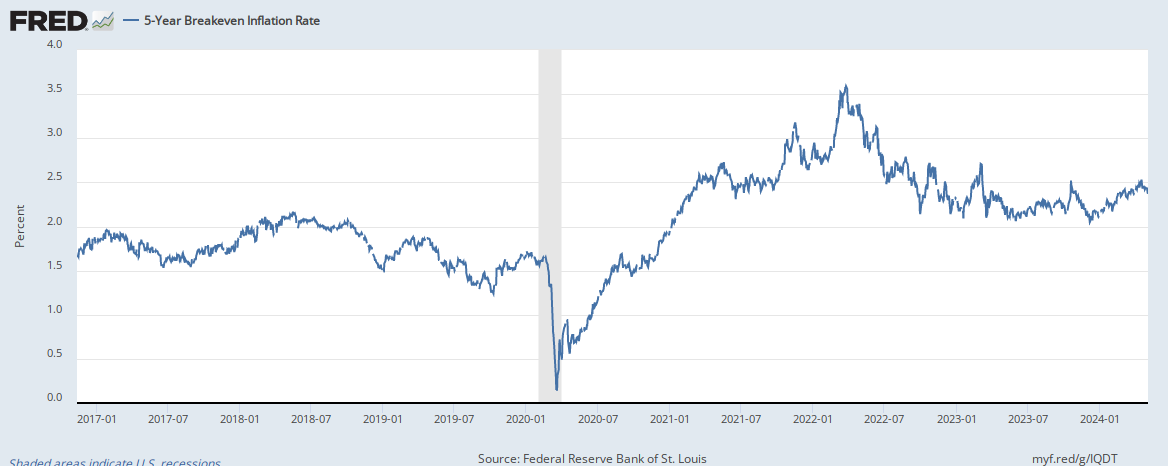

It’s more important than usual for the Fed to be guided by competent forecasters, such as the traders who influence the TIPS spread.

It looks like the TIPS spread is predicting around a bit over 4% inflation over the next 12 months, gradually moderating to 2.5% in distant decades. So maybe 2-3% total transitory inflation beyond what has already been reported and beyond the steady inflation that the Fed seems to be aiming for?

Metaculus and GJO seem to be saying something similar, at least for the short-term.

I don’t like to disagree strongly with these sources, but they’re very much near the low end of what I consider to be plausible inflation forecasts. I presume they’re more confident in the Fed’s competence than I am.

What other evidence can we find? We’ve got some evidence of the magnitude of the one-time inflation from how much the stock, real estate, and cryptocurrency markets have risen this year. This evidence is strongly confounded by other factors, such as increased savings rates. So I’m hesitant to put much weight on them. But they’re hinting at higher inflation than the forecasting sources that I mentioned in prior paragraphs.

I’ll combine those pieces of evidence with a large helping of inscrutable intuition to predict that inflation over the next two years will be in the 6 to 12% range (total, not annualized).

Labor Markets

Looking at the economy’s bottlenecks may be useful for guessing the delays between monetary changes and when consumer prices reflect those changes.

I see some signs that an unusual number of people are reluctant to re-enter the labor force for wealth-related reasons. There were nontrivial shifts in wealth recently due to fluctuations in the stock and cryptocurrency markets, leaving many seemingly ordinary people rich enough that they can retire young, or be quite picky about their next jobs. This effect seems important and under-appreciated.

The equilibrium wage has clearly gone up a good deal, yet employers are legitimately reluctant to raise wages to levels that solve the labor shortages, because some of the need for higher wages is likely to be temporary. If employers raise wages above the longer-term equilibrium rate, they’ll have serious problems with workers who won’t put up with the wages decreases needed to get back to equilibrium. I’m guessing it will take something like 8-16 more months to figure out what the new equilibrium wages are.

Longer Term?

There are still some longer-term forces that lead me to expect inflation over the next decade or two to be above 2%, likely closer to 3%. My Bond Market Bubble post still seems like the right way to analyze these effects.