Book(?) review: The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All The Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better, by Tyler Cowen.

Tyler Cowen wrote what looks like a couple of blog posts, and published them in book form.

The problem: US economic growth slowed in the early 1970s, and hasn’t recovered much. Median family income would be 50% higher if the growth of 1945-1970 had continued.

I criticized this book when I reviewed the more carefully researched Where Is My Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall (aka Josh). So I felt obligated to read The Great Stagnation and evaluate it more carefully.

Josh presents decent evidence that innovation in energy-intensive industries was strangled by hostile regulation, litigation, and similar political and social problems.

Now I’ll look more closely at how Cowen’s explanations for the Great Stagnation compare to Josh’s:

Free land

The smallpox holocaust left lots of empty or almost empty land, as a nearly free resource. That’s a clear example of low-hanging fruit that’s gone.

Josh and Cowen sort of agree here, but Josh focuses heavily on the cultural effects of a frontier mentality.

Cowen implies that the direct benefits of cheap land are important, but that effect seems to imply an earlier slowdown in growth than what we see.

Cowen also mentions the benefits of cheap land at attracting good workers from Europe. This seems more consistent with the timing of the Great Stagnation, but I’d expect the effect to fade too gradually to be measured. I’d also expect that effect to be swamped by the effect of the Nazis driving good workers to the US.

Doesn’t the brain drain from Europe hypothesis imply that whenever the effect sped up US growth, it slowed European growth? Yet I don’t see signs of the US outperforming Europe after WWII. It looks like the countries least affected by WWII experienced a slowdown within a few years of each other, and those most affected experienced similar slowdowns with a 5-year lag:

This seems to be clear evidence against any US-centric explanation. I conclude that any effects of free land became small by 1970.

Labor quality

According to Cowen, we had a steady stream of smart people leaving farms to get a university education and become more productive. 1970 is about when we ran low enough on farmers for that effect to become unimportant. Cowen isn’t very convincing on this point, but Josh has a nice graph showing that the exodus from farming ended right about 1970 – and also that an exodus from manufacturing jobs became significant around the same time – how does that differ from the effects of farming? Not to mention all those women entering the labor force.

Neither author mentions all those people from India and China who could move here and run our tech companies.

So the simplest version of Cowen’s argument seems wrong. But he hints at something special about farming: it’s an isolated environment. I suppose it’s possible that women and manufacturing workers who had lots of potential mostly got recruited to important jobs well before 1970, whereas farmers with lots of potential went unnoticed until they left the farm and went to universities. I don’t know how to evaluate that.

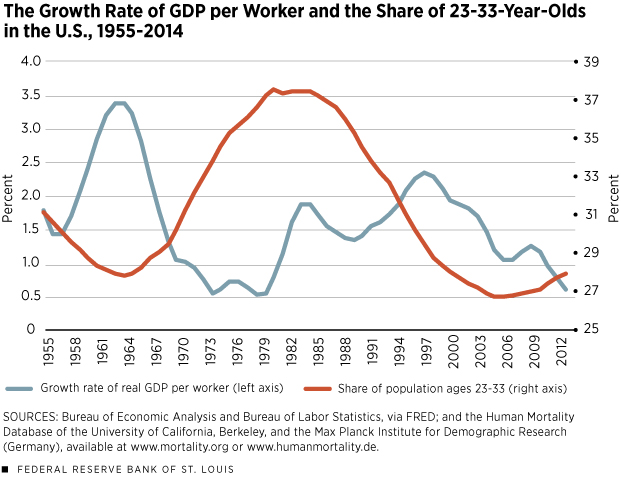

It was easy for me to find another demographic explanation that Cowen seems to have overlooked, based on the baby boom:

What is critical is the theory that young workers have relatively low human capital and that, as they become older, they accumulate human capital. … The U.S. birth rate peaked circa 1960, implying a large share of people in their 20s circa 1980. … It is important to realize that, should the theory proposed here be correct, there exists a sense in which the productivity slowdowns (especially in the 1970s) are statistical artifacts, that is, it may be that the productivity of individual workers did not change at all during the 1970s, but that the change in the composition of the labor force caused the slowdown in labor productivity.

And this paper mentions conflicting results about how important the labor pool changes were.

In sum, the more I look at labor quality issues, the more complex and confusing it looks. Cowen seems not to have noticed the confusion, possibly because he stopped researching after plucking one obvious piece of low-hanging fruit.

We stopped inventing major new technologies

This seems like the most important issue.

We stopped implementing important new inventions, except in software-related fields, due to either using up the available ideas (Cowen’s view), or because we forgot that inventions do things we like, or something.

Cowen’s main evidence for his hypothesis seems to be Huebner (2005), which uses a list of important innovations created by Bunch and Hellemans (big pdf here), to argue that peak innovation happened in 1873.

I’m somewhat suspicious of their ability to evaluate which recent innovations are important: Huebner points to “37 separate events involving space shuttle missions” as evidence that recent innovation was overstated. I’ll counter that Bunch and Hellemans’ omission of backprop points in the other direction – I believe that was many orders of magnitude more important than the median innovation they listed for the 20th century. It seems to have been invented around 1970, yet there have been large changes in the past decade in how people evaluate its importance[1]. These examples suggest that it will take more time before we reach a consensus about the rate of important innovations in the 1970s, and even then I’ll be uncertain how much of the consensus is due to groupthink.

Techno-optimist John Smart points to large disagreements about whether innovation has increased or decreased. I haven’t checked his references to figure out whether anyone has a compelling argument here, and I doubt that Cowen has checked more carefully.

Huebner also points to evidence of per-capita patents issued in the US. I’m unsure whether per-capita patents issued should be a good measure, but the mild downward trend that Huebner shows for the 20th century was decisively reversed right around the time that Huebner published. That undercuts Huebner’s thesis rather strongly, but might support parts of Cowen’s thesis: if I assume a 25 year delay between patent rates and the resulting economic growth, I can see hints that patents predict growth. If so, that suggests that Cowen timed his book to coincide with the end of the stagnation.

Josh points to a wide range of ideas that sort of look like low-hanging fruit. I’d say it’s pretty hard to respond by saying that we ran out of fruit, but fairly easy to raise questions about how low-hanging that fruit is. Often my impression is that a billion dollar investment could profitably pick a particular piece of fruit. So maybe some of the problem is that software-related fields, where million dollar investments are enough to get the low-hanging fruit, have been siphoning away the talent that ought to be focused on the bigger projects.

In contrast, Cowen’s notion of low-hanging fruit consists of a well-tended cherry orchard where the fruit is obvious. That seems like something from creationist mythology. I’d say he should look more toward Ayn Rand heroes – he says good things about Rand, but seems uninterested in her notion that innovation requires thinking more clearly than usual.

That might be harmless if he stopped there, but he goes on to talk repeatedly about “when the next era of low-hanging fruit arrives”. That’s the voice of someone who picks up crumbs from a more productive person’s feast. Innovators such as Elon Musk or Sergei Korolev don’t wait for fruit to arrive. They assemble the right tools to enable them to reach that previously inaccessible fruit.

Cowen’s attitude here reminds me of a quip (from Thomas Sowell?) about how lucky Babe Ruth was to step up to bat just when home runs were about to be hit.

Measurement error?

Both authors say the stagnation is real. But others have suggested it’s mostly due to various kinds of measurement errors, including inadequate adjustment for improved product quality, and declining interest in material wealth. Cowen points out that a sizable fraction of reported growth comes from medical care and schooling, where most of the growth looks like cost disease, not something that improves our lives. I agree that’s important, and often underestimated.

Cowen also complains about growth of useless financial activity. He gets the details rather wrong (focusing on unusually successful people, when most of the waste involves salesmen making ordinary incomes by selling the equivalent of placebos), but he seems roughly correct about the level of waste.

He mostly convinced me that the stagnation from roughly 1970 to 1995 was worse than standard measures indicate. But for 1995-2010, the situation is more complex. The standard measures report spurts of good growth, interspersed with bubbles and monetary mistakes, that don’t look much like signs of extended stagnation.

We’ve gotten large areas where value creation totally avoids economists’ attempt at measurement. Wikipedia is an obvious large example. Videophones are another: I recall my father saying in the 1980s that he’d pay something like $1000 per video call, in order to remotely diagnose mechanical trouble, sometimes saving him from needing to travel halfway across the country. Now video calls are too cheap to meter.

A less obvious category, that has larger effects on our lives, is how we meet new people.

For example, an internet support group triggered a large change in understanding of faceblindness:

As late as the mid-1990s, medical literature reported less than two hundred cases, and only three of those were people born with it – so few some researchers expressed an opinion that one could not be born with it. … Well, in the spring of 2006, two tests made upon random samples from general populations were finally given, and they revealed a very surprising number: About two percent of the population is face blind!

The handful of people before the 1990s who knew they were born faceblind didn’t have a reasonable way to broadcast their desire to meet similar people, so nobody noticed signs that faceblindness was more than a freak accident.

I suspect this illustrates a large class of improvements in how people find like-minded people to interact with, for ordinary social purposes, for starting new businesses, and for solving obscure problems. This value might be large compared to the effects of cost disease, so it’s hard to say whether recent growth in our wellbeing has been over or underestimated.

Cowen has a good description of how the 2008 financial problems were caused by widespread complacency about real estate prices and banking risks. That’s evidence that the economy was doing worse than we expected. But those are typical features of a bubble, and only required complacency about a few industries (e.g. maybe people were too optimistic that immigration would fuel housing demand). Cowen’s attempt to tie that to the Great Stagnation is not at all convincing.

Advice

Given his diagnosis, I’m unsurprised that his advice is unambitious. Here’s the part I found most interesting: “Raise the social status of scientists.”

That seems puzzling – my impression is that the social status of scientists remains fairly high. I see few signs that science productivity has declined. I’d say a bigger problem has been the decline in status of engineers – at least those who operate far from computer-related fields.

But when he gives an example, it’s Norman Borlaug, who straddles the divide between scientist and engineer. I certainly agree that Borlaug deserves higher status, but I disagree about how to generalize that. (Borlaug grew up on an isolated farm, and appears to have just barely managed to get to a university; that seems to be a bit of evidence in favor of Cowen’s story).

Conclusion

Cowen’s explanations for the stagnation are mostly unconvincing guesses that are somewhat less than half right. He seems to have entered the field, gathered the first few semi-ripe fruits he saw, and moved on without spotting the juicier fruit that was partly obscured by some leaves.

Read Where Is My Flying Car? instead.

[1] – I decided in the early 1990s that backprop was pretty important. But I also decided then that genetic programming was almost as important; in hindsight, that looks foolish, so I’m not sure how much of my early recognition of backprop’s importance was due to luck versus skill. A key consideration is how well the algorithms scale up to large datasets; very few people were able to predict in the 1990s that backprop would scale well but genetic programming wouldn’t.