Book review: Warnings: Finding Cassandras to Stop Catastrophes, by Richard A. Clarke and R.P. Eddy.

This book is moderately addictive softcore version of outrage porn. Only small portions of the book attempt to describe how to recognize valuable warnings and ignore the rest. Large parts of the book seem written mainly to tell us which of the people portrayed in the book we should be outraged at, and which we should praise.

Normally I wouldn’t get around to finishing and reviewing a book containing this little information value, but this one was entertaining enough that I couldn’t stop.

The authors show above-average competence at selecting which warnings to investigate, but don’t convince me that they articulated how they accomplished that.

I’ll start with warnings on which I have the most expertise. I’ll focus a majority of my review on their advice for deciding which warnings matter, even though that may give the false impression that much of the book is about such advice.

The 2008 Banking System Problems

The book describes a Cassandra who accurately predicted Citigroup’s near-collapse in 2008. Alas, there are thousands of people with similar competence who are trying to attract attention (or manipulate markets) by warning that there’s something wrong with a particular company. I make my living largely by distinguishing which companies are good investments. I ignore most such Cassandras, because there’s too little difference between their prescient warnings and their mistaken ones. I don’t buy the authors’ vague hints that they’ve identified something special about this warning.

Nitpick: the chapter title implies that the banking problems caused the recession – a controversial belief which I think is probably wrong.

Madoff

Many finance experts smelled something rotten about Madoff, but no Cassandra found the kind of evidence that would justify an arrest.

Part of the problem in this case is that Madoff demonstrated enough business skill that he could have instead chosen a strategy of getting rich by ripping off investors more honestly and legally. His fraud doesn’t look like a simple desire for wealth. It looks more like he wanted even more of something (the appearance of being unusually helpful to clients? the appearance of never making mistakes?). That helps explain why a sensible SEC might decide he looked sufficiently different from their profile of a con man to be not worth investigating.

I applied the book’s “Cassandra Coefficient” to this case (see this footnote for details), and concluded that the book’s advice would have led me to give somewhat low priority to warnings about Madoff.

I suspect the authors would disagree with how I applied some of their “coefficients”, but I don’t think they should be surprised that their advice generates disagreement.

Fukishima

The chapter on Fukishima provides lots of detail on how nuclear reactors failed after being hit by a tsunami. Yet the chapter also mentions a much simpler way to understand why people died because officials ignored warnings about tsunami sizes: the tsunami crushed people in tsunami evacuation sites.

I’m going to go out on a limb and claim that people who choose tsunami evacuation sites have less excuse for underestimating tsunamis than do people who choose nuclear sites. So, why did the authors devote many pages to nuclear technology, but only two sentences to evacuation sites? My guess is they’re aiming at readers who care about something other than the harm caused by catastrophes.

Many people apparently warned that standard tsunami precautions in Japan were inadequate, because they overlooked evidence from the tsunami of 869. At least one person was believed, and as a result a nuclear site was adequately protected. What explains the difference? It sounds like the successful Cassandra was more confident, or maybe louder? I’m disappointed that the authors didn’t find any other differences.

Climate Change

The book convinced me that there’s less of a consensus about climate change than many mainstream sources had led me to think, and that there’s at least one competent expert who says the IPCC underestimates the risks.

But expertise at identifying problems doesn’t imply expertise at solving them. The Cassandra in this chapter shows little expertise, and no sign of being data-driven, when describing how society would handle flooding of major cities.

Current Warnings

The book does a fairly good job of portraying Eliezer Yudkowsky’s concerns about AI.

But I saw two places where the authors sound confused:

Nearly every computer and neural scientist with expertise in the field believes that the intelligence explosion will happen in the next seventy years; most predict it will happen by 2040.

No, less than half predict an intelligence explosion. The authors may be confusing that with predicting human-level intelligence, but even with that interpretation, there’s more expert doubt than the book claims.

[Eliezer] envisions … a system of checks and balances so that advanced AI growth is auditable and controllable

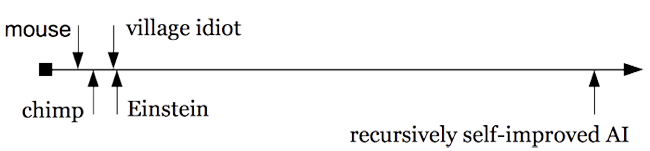

That sounds like the authors imported ideas from politics without adequate thought. The amusing graph that they reproduced a few pages back:

should have suggested to them that in Eliezer’s predicted scenario, relying “checks and balances” would be about as effective as mice trying to control humans by creating checks and balances among humans. In contrast, the book Beyond AI advocates something resembling checks and balances to handle AI, but his reasoning depends on rejecting Eliezer’s claim that an intelligence explosion will enable a single AI to take over the world.

Those two mistakes are nontrivial, but they’re less embarrassing than a typical layman’s summary of Eliezer’s ideas.

Pandemics

The book is disappointingly vague about whether authorities are adequately preparing for plagues. Sure, they quote some arguably well-informed Cassandras who say that precautions are woefully inadequate. But I’d expect to see such complaints regardless of how well or poorly authorities were doing.

CRISPR

The chapter on CRISPR starts with a depiction of a clone army. I’m a little unclear whether that army is supposed to be scary because it would be powerful, or because it would be fragile (due to the lack of diversity), or simply because it’s unfamiliar enough that readers can pick whatever scary interpretation they want.

The book reports a Cassandra who more clearly understands the relevant new technology than is the case for any of the other scenarios that they cover, and yet the warnings sound like Hollywood fantasy. There’s little controversy here about what the new technology can do, and plenty of confusion about what people want.

Disclaimer: I own stock in CRISPR companies.

Failed warnings

The book devotes a little attention to failed warnings such as the Y2K crisis, or the population bomb, which predicted an increase in famines starting in the 1970s:

It’s unclear how much the book’s advice will help avoid similar mis-predictions in the future.

What do I do with the advice?

What do I get when I try to apply the book’s advice to other warnings?

I started to write detailed analyses of how I could apply their criteria to warnings such as:

- Al Qaeda’s plans in the late 1990s to attack the US

- warnings from Broda Barnes and John Lowe about underdiagnosis of hypothyroidism

- the dangers of dihydrogen monoxide

- the IPv4 depletion crisis

But I found that I’d be mostly repeating the same doubts I mentioned about the Citigroup and Madoff warnings, and responding to each warning with a firm “maybe”.

To the extent the book’s advice is helping me with these warnings, it’s by encouraging me to be more uncertain. That’s a good effect, but I’m puzzled as to whether the authors want that result – they seem to encourage more confidence in individual Cassandras and in our ability to identify more Cassandras, yet they seem to practice uncertainty in their overall evaluations of each warning.

Conclusion

The books says the more credible Cassandras are data-driven, yet the book seems mostly anecdote-driven.

For data-driven advice about forecasting, read Tetlock or Nate Silver. That’s more useful than Cassandra-specific advice.

If you’re tempted to become a Cassandra, this book will warn you that, unless you’re unusually persuasive, you’ll probably be punished for your efforts. So don’t just be careful to find evidence that you’re right, be careful to also deliver your message in a manner that people will listen to. Then people will merely downplay the risks that you helped them avert.

The authors’ primary goal may be to create an office within the U.S. government to handle unusual warnings. That certainly seems to be cheap enough to be worth trying, but the book provides little hope that such an office will make much difference.

Footnote

This footnote is mainly written for people who have read the relevant chapters of the book, particularly to make fun of politely disagree with those who think these criteria represent valuable insights:

| Supports warning | Clearly not a warning sign | Unclear, probably doesn’t support warning |

|---|---|---|

| Response Availability | Initial Occurrence Syndrome | Magnitude Overload |

| Complexity Mismatch(?) [1] | Erroneous Consensus | Outlandishness |

| Profiles in Cowardice | Diffusion of Responsibility | Invisible Obvious |

| Satisficing | Agenda Inertia | Inability to Discern the Unusual |

| Proven Technical Expert | Orthogonal Thinker | Ideological Response Rejection |

| Off-Putting Personality | Scientific Reticence | High Anxiety [2] |

| Data Driven | Personal or Professional Investment [3] | |

| Questioners | “Now is Not the Time” Fallacy | |

| Sense of Personal Responsibility | ||

| Non-Expert Rejection |

[1] – I put a question mark by Complexity Mismatch because the authors claim the SEC was put off by the complexity of the reasoning behind the warnings. I find that misleading, because the SEC could have caught Madoff without understanding the complex reasons. They could have noticed that many experts disbelieved Madoff, and those experts could have suggested (did suggest?) simple ways to catch some Madoff lies.

[2] – where would I get decent evidence of anxiety levels for any Cassandra I don’t know personally?

[3] – by the standards of professional/industry/expert investment, this criterion clearly provides the opposite of the Cassandra stereotype. I’m unclear on whether some of Madoff’s (amateur) customers qualified as having an investment which caused them to attack the Cassandra.

Or, to summarize by category (as the book does when it “quantifies” coefficients):

the warning: low; the decision makers: moderate; the Cassandra: high; and the critics: low.

Pingback: Rational Feed – deluks917