This post is about the combined effects of cheap solar energy, batteries, and robocars.

Peak oil is coming soon, and will be at least as important as peak whale oil; probably more like peak horse.

First I noticed a good article on the future of fossil fuels by Colby Davis. Then I noticed a report on robocars by Rethinkx, which has some fairly strong arguments that Colby underestimates the speed of change. In particular, Colby describes “reasonable assumptions” as implying “Electric vehicles would make up a third of the market by 2035 and half by 2040”, whereas RethinkX convinced me to expect a 2035 market share of more like 99%.

tl;dr: electric robocars run by Uber-like companies will be cheap enough that you’ll have trouble giving away a car bought today. Uber’s prices will be less than your obsolete car’s costs of fuel, maintainance, and insurance.

As I was writing this post, a Chinese official talked about banning gas-based cars “in the near future” (timing not yet decided). If only I had bought shares in a lithium mining company before that news.

energy costs

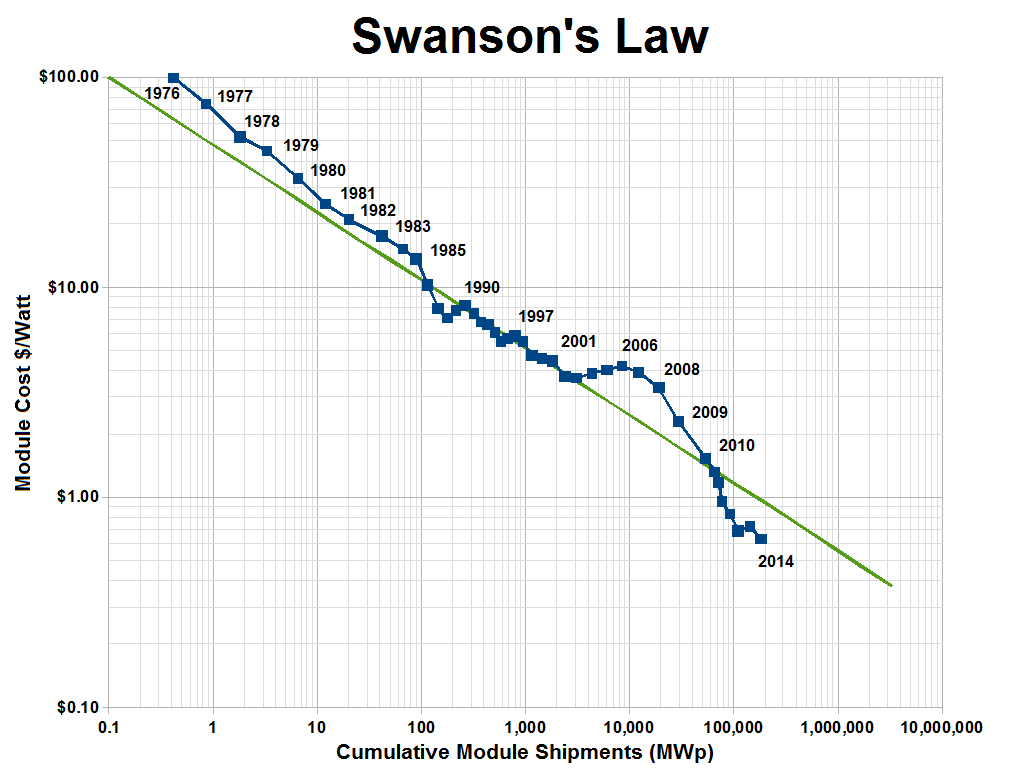

Solar costs have dropped at a Moore’s law-like rate. See Swanson’s law.

Experience curve effects seem to provide good guides to trends of declining manufacturing costs. Solar is likely to experience one or two orders of magnitude increase in cumulative installations over the next 10-20 years before its growth slows, so its cost should drop 50% to 75% from today.

According to table 1a in this EIA report, a 50% drop in cost means that the levelized cost of solar would be around $37/MWh, which matches the variable cost of running a natural gas plant [1].

Wind energy costs have also been declining, although less reliably than solar costs. My best guess is that average wind costs will be similar to solar costs in 2030, with significant regional variations due to differences in available wind and sun.

According to RethinkX, global oil demand will drop 30% between 2020 and 2030 due to electric cars, with crude oil prices dropping to $25 a barrel (i.e. about half of current prices). That looks pretty plausible to me.

A puzzle: the stock market doesn’t see the oil price drop coming. Futures prices predict small price rises through 2025, and many companies related to oil drilling are priced as if oil drilling will do almost as well they have in the past over the next 10+ years.

My guess is that experts on fossil fuels pay little enough attention to other industries that they’re currently unprepared for the effects of large changes in those other industries, and, like most people, they pay too little attention to experience curve effects.

That’s consistent with them using heuristics that work fairly well: the base rates are pretty low for an industry as big as oil declining 30% by volume with little warning. Plus, electric cars have been hyped for long enough that many people are tired of hearing about it, and suspect that most of the hype is motivated by nonfinancial concerns.

It seems like an unusual coincidence that self-driving software and battery technology are both reaching competitive levels for cars at roughly the same time, and that solar and/or wind are available just in time to ensure affordable electricity for them. And without something Uber-like, I’d have to think about consumer reluctance to deal with recharging batteries.

The stock market has already announced that coal is a declining industry. Natural gas has become competitive enough to hurt the coal industry. Existing coal plants will likely keep running for their scheduled lifetime, new ones will be quite rare.

The outlook for natural gas is less clear. A lot depends on whether batteries become cheap enough to shift solar power from sunny times to cloudy days and/or night.

Lithium ion battery prices have been dropping at something like 14% per year over the past decade [2], and are starting to become competitive with gas under a few conditions. But my guess is that batteries won’t get cheap enough until about 2030 to compete with building new gas plants for regular night use. We’ll need gas plants for much longer than that to handle cloudy days. And as long as those plants are needed, their variable costs seem likely to be lower than the cost of solar plus batteries well past 2030.

So I expect solar to cause natural gas plants to completely shut down for several hours in the middle of sunny days in most regions. That will probably cause something like a 10% decline in this use of gas. I’ll guess that wind will replace a similar amount. Since 36% of U.S. gas goes to electricity [3] (I’m too lazy to check for global numbers), I’ll guess that means something like a 7% reduction in gas use compared to the trendline by 2030. That will likely be offset by some demand for replacing coal plants that get retired, so I predict a moderate decline in the combined output of coal and gas, but not a decline in gas.

Could politicians stop these trends? Donald Trump often talks like he wants to damage the environment in order to protect coal miners, but his committment to fighting renewable energy seems weak. Just look at poor Carl Icahn, who supported Trump in hopes of protecting some oil refiners from the ethanol lobby. It sure looks like Trump has abandoned Icahn. Maybe coal miners have more political clout than Icahn, but they’ve got a weaker case for their goals being compatible with the public interest.

The U.S. government is trying to protect U.S. workers from cheap foreign solar, but that looks like it will only cause a modest slowdown in solar adoption in one country.

Could any new sources of demand for fossil fuels offset these trends? Delivery drones? No, it looks like they’ll probably use electricity. Feedstock for Drexlerian assemblers? Maybe, but I don’t have much of an argument that such demand will be large compared to current fossil fuel use. Robots, rockets, or flying cars? I can’t quite see them being common enough by 2030 or 2040 to much affect energy use, and that’s as far into the future as I hope to predict in this post.

Implications for global warming: the possible harms seem a bit less threatening, but it’s also becoming cheaper to reduce CO2 emissions. The cost reduction seems larger than the risk reduction, so I’m shifting to more support for large reductions in CO2 emmissions in the 2030-2040 time range. (Don’t forget other sources of warming that will eventually overshadow CO2).

Industries affected

Oil drilling companies look mostly obsolete. High cost drilling, such as deep-water drilling, is being shut down now, probably permanently. Other drillers, and other oil companies, are likely to shrink significantly.

Batteries and lithium miners will prosper, although the stock market already reflects a fair amount of that.

Auto manufacturers won’t do very well: we may want fewer cars, because the mileage driven over a car’s lifetime will increase at least as much as the demand for rides. RethinkX sees a large drop in cars built; I expect a more modest drop.

Auto dealers may shut down, as something like Uber may become more convenient than owning a car (except in very rural areas). (Although I’m less confident than RethinkX is about the speed at which individual car ownership will be abandoned).

Auto insurance companies become mostly obsolete. The accident rate will decline drastically, due to robocar safety. Uber or Tesla or Starbucks [4] or whoever owns the typical car may need a bit of insurance, but will only have much reason to deal with insurance companies for unusually costly collisions. And presumably most of the liability will fall on the car’s manufacturer.

Railroads will do poorly, because their trucking competitors will drop their prices by more than half, while also increasing their speed, flexibility, and reliability. The trucking industry will do well, but I won’t bet that existing companies will be adaptive enough to be the ones that benefit.

There will be important shifts in where housing prices are high. I’m probably still oblivious to many of those shifts. Two shifts I do see are that oil and coal producing regions will have weaker prices, and neighborhoods near subway stops will have weaker prices compared to more distant neighborhoods.

Municipal buses will look pretty silly if politics keeps them around in anything like their current form. Uber is likely to undercut their fares, while being obviously more convenient.

Electric utilities, chemical manufacturers, steel, aluminum, etc will get some modest benefits from reduced energy costs.

Airlines and airports will be helped by lower fuel costs and faster traffic to airports. That effect will be partly offset by cars becoming more competitive with planes for short distance routes.

Toll roads are likely to prosper due to increased traffic volume.

What will happen to the mobile home industry? Cheaper self-driving mobile homes look feasible. But demand might be low enough that the industry will be slow to adapt.

Please don’t treat this post as sufficient advice for making any investment. This kind of analysis is only a modest part of how I make any investment decision.

Disclosure: I own shares of a number of solar, solar-related, and wind companies. I own stock in BYD (batteries, bought as a result of the research that turned into this post), in an airport, and in a toll road company. I’m short oil (the December 2025 futures), two large oil well services companies, and two car rental companies.

[1] – “variable cost” means the difference between running the plant and keeping it idle. EIA imagines that natural gas prices will rise, so their assumptions about gas imply that most gas plants should be shut down in the middle of sunny days if my estimates of solar costs are accurate. Note that the EIA’s cost estimate for solar farms entering service in 2022 is higher than Lazard’s estimate of current (2016?) costs. But I expect the price to be determined by market conditions closer to when construction starts – 2019 or 2020 for a plant coming online in 2022.

[2] – see here for a decent graph, and Lazard’s analysis for lots of details about current costs.

[3] – See this really nice chart from LLNL. A majority of natural gas use is for industrial / commercial / residential purposes that I’m assuming are somewhat expensive to switch to electricity.

[4] – RethinkX suggests that Starbucks might find it cheaper to provide free rides in hopes of selling coffee to riders than it is to own stores. I find this somewhat plausible. It might look more bus-like than car-like, but the distinction between buses and cars will likely blur.

I’ve got a wierder business plan to suggest: combine Uber pool with a dating / friend finder app. The app matches riders as mostly blind dates, based initially on profile info, then later based on inferences from riders’ responses. It prompts the riders with some suggestions about topics they’ll be mutually interested in discussing. Riders tip the app if they’re satisfied with the match, but can free-ride if they want. The app motivates them to tip by offering better service to good tippers. Does better service mean faster pickup times? Or getting matched with higher-rated riders? Or maybe if you tip really well, the app pays someone who’s a good match for you to accept an inconvenient route so that you can meet?

The incentives won’t be ideal – the app will optimize more for the quality of the average match, when I’d want it to focus more on the occasional great match. Existing dating services have sufficiently poor incentives to provide good matches that it won’t take a great algorithm to beat them.

Thanks for the charts. I do believe in experience curve effects, and hadn’t noticed the trend lines for solar.

Anecdata: the local (Mountain View) school district has installed solar recharging stations in many of their parking lots. Apparently batteries are cheap enough that they don’t have access controls on the rechargers, and signs are posted telling the public that the electricity is all renewable, and not saying that the public isn’t allowed access.

I think you overestimate the flexibility and rationality of electric companies, which are highly regulated, to the point of being state-managed. Merkel recently built a bunch of coal plants to pander to the coal miners. But also to pander to the Greens by shutting down nukes. When the Greens first scheduled this, did they plan coal plants? Did they plan anything?

On the other hand, you make a good point that if cars are centralized, the owner can vertically integrate; in particular build an optimal power plant, pretty much regardless of what the grid does.

Douglas, I’m rather confident that problems with politics and corporate bureaucracy won’t delay these trends by more than a few years.

Northern Europe is a crappy place to install solar energy – it gets less sunlight than even most Canadian cities (see this global map).

If Germany can’t reliably get solar electricity from Spain or northern Africa, then it may make some sense for them to build more coal plants.

Note that England is shutting down coal faster than I would have thought is plausible (“British coal consumption fell by 52.5% in 2016”).

China is less hobbled by political pandering, and is more important than Germany.

Would you care to suggest a bet on coal use in 2030?

Bureaucratic inflexibility will somewhat impede the shift to solar and wind, by not encouraging the time-shifting of electricity use to coincide with sunlight and/or wind.

The marginal value of electricity will drop to zero in the middle of sunny days at its source in the big solar farms. Ideally, electric companies would charge almost nothing for electricity then, and users would shift a modest amount of demand to that time. I expect the grid operators to be slow to alter pricing rules to do that.

I did some research, when writing the post, into whether Uber could bypass the grid, and get its batteries charged directly at the solar farms. I concluded that it will happen in some places, but I can’t predict whether it will be sufficiently widespread to be important.

Brad Templeton has some good ideas about how robocars will affect car makers.

Pingback: Where Is My Flying Car? | Bayesian Investor Blog

Pingback: Another AI Winter? | Bayesian Investor Blog